Patrol with EUMM on the “border” between Georgia and South Ossetia

(B2 in Tbilisi) B2 accompanied a patrol of the European Union Monitoring Mission in Georgia (EUMM), near the demarcation line with South Ossetia. Unarmed, these observers, many of whom are former or current police officers, are working to reduce the level of tension

EUMM Georgia is made up of 200 observers, from 27 of the 28 member countries (Slovakia has no staff at the time of our visit, but usually deploys some). Present since October 2008, following the fighting between the Georgian army and the South Ossetian and Abkhazian rebels, supported by the Russian army, they are the last channel of dialogue between the parties to the conflict. They patrol throughout Georgia, largely favoring the demarcation lines with the 20% of the territory occupied by Russian forces and their allies.

A tense situation

Hardening borders...

Georgians and many media often speak of advancing “borders”. The South Ossetians and the Abkhazians, supported by the Russians, would gradually advance the line by adding barbed wire around a field here, a barrier there at the entrance to a village cut in two. For the EUMM spokesperson who welcomed us to Akhmazi, " it's not a question of advancing borders but of hardening borders »: the infrastructures evolve with the multiplication of new cameras, watchtowers, physical obstacles, perceived by the Georgians as so many threats and provocations.

… And impose themselves de facto

On the border post that we were able to observe, the traffic is relatively fluid. 400 people cross it every day. South Ossetian guards check the vehicles: passenger passes, contents of the trunk, absence of weapons or dangerous equipment. In the second curtain, Russian border guards are present. When foreigners show up without the necessary documents, they are simply expelled. But the Georgians are arrested and tried. “An unusual practice for someone who has worked at a border post in another country », stresses a member of the EUMM.

The term remains a complicated subject. If the South-Ossetians and the Abkhazians speak of “border”, the Europeans prefer the term “administrative demarcation line” (administrative boundary line). The Georgians themselves speak very clearly of “occupied territories”.

Prohibitions maintained

Deployed following the fighting in 2008, the EUMM falls within the framework of the six-point agreement negotiated at the time by the European Union with the belligerents. Two of these points are however still not respected, a little more than ten years later: the European observers do not have access to the occupied territories and the Russians have not withdrawn. If Moscow remains discreet about the numbers present in South Ossetia and Abkhazia, the military balance estimates the number of their soldiers at around 7000, making Georgia the second theater of operations for Russia in terms of personnel after Ukraine (28.000 men) and ahead of Syria (5000 men).

The people taken hostage

For Georgians, whether they are on one side or the other of the demarcation line, this situation creates great precariousness. Traffic permits are only valid for three years and there is no guarantee that they will be renewed over time. Worse still, the de facto authorities can suspend the relative freedom of passage at any time. This is what happened on January 11 when South Ossetians and Abkhazians decided to close the borders to avoid the arrival of the H1N1 flu, which killed 15 people in Georgia. Those on the wrong side, including students who came to visit their families to celebrate the New Year, were stuck for two months without recourse. About 140 people were still exceptionally allowed to go out, for major health reasons. Enough to maintain, according to a member of EUMM Georgia, a "psychological pressure".

Explicit Russian presence

From the road that goes from one side to the other of the demarcation line, the camps of the Russian border guards (1), are perfectly visible. In each of the two territories, 19 of these camps, perfectly identical, are distributed along the borders. Inside, the Russians live with women and children. So many indicators suggesting, as one EUMM member points out, " that they want to show that they are here for a long time ". The real Russian military bases are further inland, a good twenty kilometers from the border.

EUMM Georgia on the front line

Europeans in contact

As early as 2008, the European Union negotiated within the framework of the Technical Arrangements (Technical Arrangements) with the Georgian authorities that the latter do not deploy too heavily equipped police, see the army, near these areas. EUMM is responsible for monitoring and informing the actors about what it observes. A way to reduce tension. If the Russians have been called upon to follow a comparable logic, they have not yet done so. Similarly, NATO does not let its personnel approach these areas, to avoid any accusation of espionage or provocation. The Georgians have nevertheless deployed a special police tasked with monitoring flows to and from South Ossetia and Abkhazia. This does not depend on the border guards… Since no border is recognized.

EUMM's missions

EUMM Georgia's mandate sets it four missions: monitoring and stabilizing the situation; encourage the standardization process; multiply contacts and projects to reduce tensions; enlighten the political decision of the European Union. If since 2008 the situation has been relatively calm, it is nevertheless difficult to speak of progress. No possible solution is emerging.

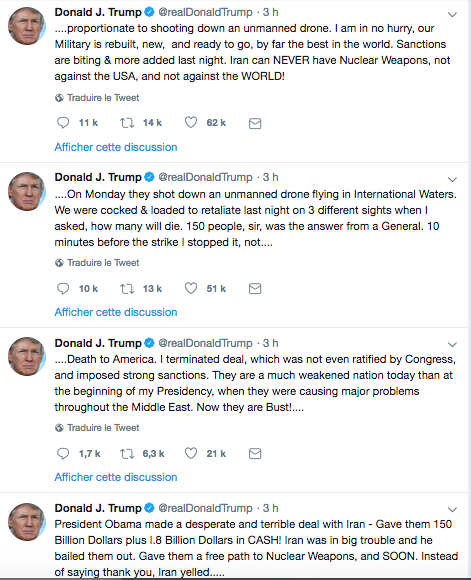

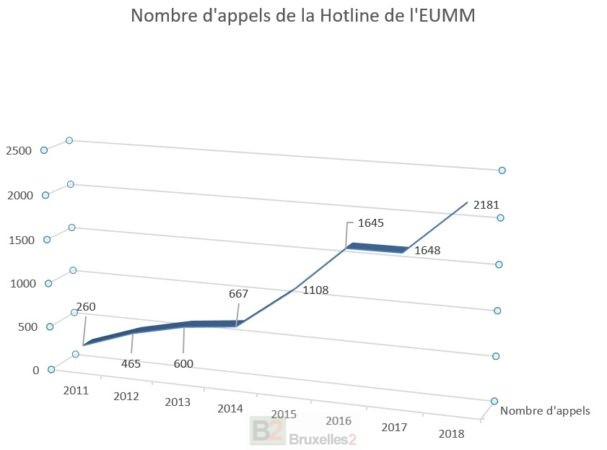

Hotline

In February 2009, the parties to the conflict together with the EU, the OSCE and the UN adopted an Incident Prevention and Response Mechanism (IPRM). This must allow a dialogue between the belligerents but works intermittently. The hotline set up by EUMM Georgia in this context seems to be the most concrete and effective tool. The only channel for operational dialogue, it allows European observers to have direct contact with identified interlocutors on both sides. In the event of an incident, both parties can use it as an information relay: if the Georgians cannot call the South Ossetian security forces directly, they can ask EUMM to do so to obtain information about a specific event. Enough to avoid misunderstandings when the South Ossetians train in shooting, for example.

A mission difficult to understand

Georgian frustrations

Many Georgians sometimes feel that the EUMM teams do nothing. Patrolling with their blue vests, unarmed and unable to intervene by force, their mission may seem futile. They sometimes struggle to understand, for example, that EUMM members direct them to sources of funding for humanitarian projects. Why don't Europeans do it themselves? Because that is not part of their mandate. The spokesperson for the operation admits this difficulty and multiplies educational and information efforts, in order to better explain the role of EUMM, particularly with regard to intermediation between the different parties to the conflict.

A lack of media coverage

For lack of news (and explosion of violence?), EUMM struggles to publicize its activities and its small daily successes. However, the situation in Georgia remains particularly important for Europe, against a backdrop of tensions with Russia and Tbilisi's integration project into the EU and NATO. To encourage local journalists to highlight the events, EUMM is also organizing a prize for peace journalism (peace journalism), which rewards committed and ethical reporting, escaping Manichaeism and ease.

(Romain Mielcarek)

(1) This service is part of the Russian security service better known as the FSB.

Read also:

- File No. 44. EUMM Georgia. Europeans against Russia

- Our file The observation mission in Georgia “EUMM Georgia”

- Dane appointed head of EUMM Georgia

- Our report in 2008, Back from reporting in Georgia, stories…