[Yugoslavia Memory of a disaster] Paul Garde: 1990, a somewhat messy Europe

(BRUXELLES2) Summer is conducive to thinking and putting together notes that you haven't had time to put together. In August 2008, I spoke at length with Paul Garde, a historian, professor of Slavic linguistics at the University of Provence, specialist in the Balkans, author in particular of "Life and death of Yugoslavia" (Fayard, 1992 reed. 2000) or "End of the century in the Balkans 1992-2000. Analyzes and chronicles (Odile Jacob, 2001). His point of view on the genesis of the Yugoslav wars and the various European implications is still fully relevant today and this return to history makes it possible to understand the role played by Europe in a region which remains the crucible of EU foreign and defense policy.

Compare the 1990s and 2010s?

There is quite a big difference between today and yesterday. In 1990-1091, the different countries of the European Community had different positions and for some time maintained great differences. It was completely illusory to think that there could be a European policy. We didn't notice it at first. (…) And we did not pay attention to this region. Germany, for example, only began to take an interest in the question with the war in Slovenia. Genscher (the Minister of Foreign Affairs at the time) on a mission, had to divert to Slovenia (see Memoirs). It was then that he really realized the problem. As in the revolutionary period, in 1991, things were changing at breakneck speed.

"At the beginning (war in Slovenia), it worked. Because the two parties involved had the same interest in quickly coming to an agreement. Immediately afterwards, it all fell apart."

But was there a European reaction?

Yes. At the time of the war in Slovenia, Jacques Poos even said “the hour of Europe has arrived”. It worked because the two parties involved - Slovenia and the Yugoslav Federation - had the same interest in reaching an agreement quickly, on the back of Croatia moreover. The intervention had been decided by the Yugoslav presidency. But Milosevic had recognized that it was in his interest for Slovenia to leave in order to be able to crush Croatia. Most major European countries are roughly on the same line. There could be a European policy. Immediately afterwards, it fell apart. In July 1991, the major European countries took opposing positions. The French and the British allowed themselves to be carried away by prejudices dating from the 1914 war. And (above all) they believed that the Serbian side was acting to maintain Yugoslavia. When it was quite the opposite. Milosevic wanted the destruction of Yugoslavia. They did not see an attack there. This is the meaning of the quarrel between Europeans in the second half of 1991, Mitterand having openly sided with Serbia while Germany demanded recognition of Croatia. It was a very, very dangerous moment. I believed that Europe could burst. Then Mitterand, Major and Kohl understood that it was more important to defend a European unity, to recognize Croatia, to send, at the end of 1991. The decisions were effective to a certain extent – with a ceasefire in Croatia – but not very effective with the war in Bosnia. We then found the same cleavage. And again, the European countries floundered.

You seem severe on the role played by Mitterand

Yes. There was a complete blindness of Mitterand who did not see the aggression and, in fact, encouraged the aggressor. At the end of November 1992, Mitterand reminded Croatia of its participation in the Nazi camp during the war, not Serbia. There was, on the French side, a pro-Serbian tropism, a Jacobin prejudice and a lack of understanding for all that is federalism and a hostility to independence. The replacement of Mitterand by Chirac was important. Likewise, that of Bush Sr. by Clinton. They ended up producing joint decisions and deciding on a joint intervention during the summer of 1995 – after three years of war and massacres – with the Dayton Accords. But the decisive intervention came from the United States (not from Europe). Russia was then out of the game.

"Europe has had quite a few initiatives

but did not succeed in acquiring the means to impose its will"

Finally, the role of the Europeans…?

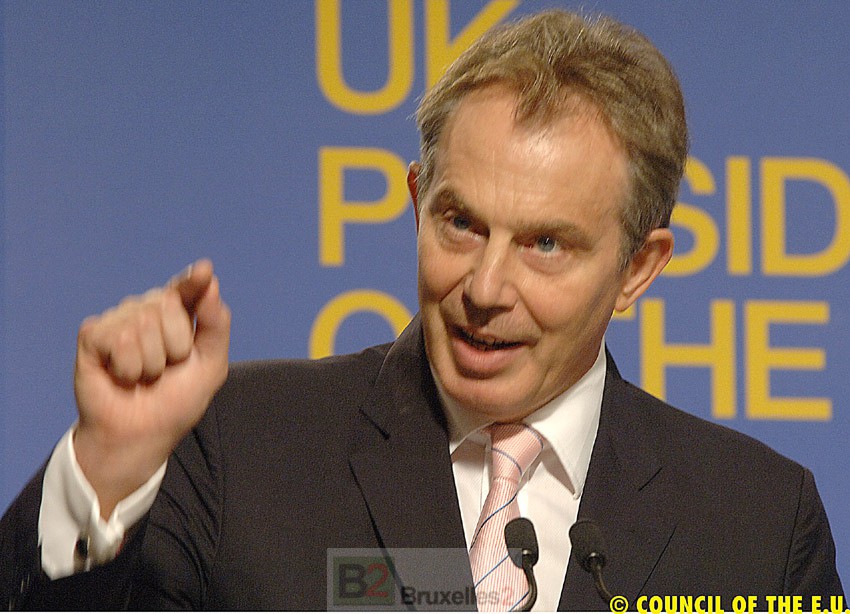

Europe has had quite a few initiatives but has not succeeded in acquiring the means to impose its will. (…) European countries have given a lot. They provided the troops a lot. But the political (and military) impetus was American. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, America played a key role. Europe has indeed been called upon, but for a minor role: in Mostar. All the tactics were led by the USA, like the idea of reconciling Croats and Bosnians to better fight against the Serbs. And the civilian performers were… Europeans. There have always been European managers. It continued afterwards. In Bosnia and Kosovo, all the senior UN officials and chief administrators were Europeans. But they were acting on an international mandate. With an American direction despite everything. In Kosovo, in 1999, we witnessed the greatest European unanimity. Chirac, Blair (who replaced Major)…all agree on the war in Kosovo. Russia did not count for much yet, these were the last years of Yeltsin. The most reluctant country would have been Greece. The future members (Romania and Bulgaria) accepted European decisions – such as prohibiting Russians from flying over the territory – when they could have helped the Serbs.

Is the game the same afterwards?

At the end of the 2010s, the United States was entangled in Iraq (NB: and Afghanistan) and appeared powerless. While in 1990, they appeared with Iraq-Kuwait, all powerful. Russia has regained the hair of the beast, with Putin, its game on gas. The Balkan situation which led to the 1914 war – great powers opposed to each other with each of the Balkan clients – we feared for a moment that this would reform in 1991. But European cohesion was stronger and the American role remained strong. This Balkan configuration is in the process of reforming. The EU and the USA are bothered because locally, there can only be one solution, independence. Because we can't really believe that Kosovo will once again be under the control of Serbia. But there is an international configuration such that they are afraid to proclaim this independence, if Russia - in the process of becoming a great power again - supports Serbia and leads to make it more intransigent.

Does the traditional carrot of Europe, that of EU membership, play a role?

Yes. Since 1995, and the end of the war in Bosnia, Europe has played a very big role, because of its enlargement projects. From the beginning, all the Balkan countries had only one dream, to join the European Union. Europe has laid down criteria, in particular for collaboration with the Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY). And countries have done what they can to meet the criteria. Croatia, which had handed over all its criminals except Gotovina, thus suffered the interruption of negotiations. And Gotovina was delivered. It was applied brutally. But for 10 years, the desire to join has been one of the main assets and levers. And it still continues almost everywhere in the Balkans. But we never know. We felt, on the Serbian side, some hesitation. The will, very strong for a time, seemed to weaken. It is not certain that the will to join the EU is so strong, especially in Serbia. This risk of weakening is linked to the loss of image of Westerners.

In Bosnia-Herzegovina, the situation remains more difficult, do you believe in a new risk of conflict?

No. The problem is not military. There since 1995, international troops are present. The status quo is independence materially. It is de facto independent and guarded by international troops. Frankly, I don't believe in the danger or specific risk of war. People are fed up with military adventures. The danger is Russian diplomacy (Abkhazia, South Ossetia, Transnistria) to the detriment of Ukraine, Georgia and Moldova – and in the Balkans with the proclamation of Republika Srbska. But it could stop participating in joint bodies. This would pose serious diplomatic problems.

"We have not yet succeeded in convincing (and informing) the Serbs of all the horrors

which have been committed in their name."

In the enlargement policy, the EU is applying too rigorous a policy, in your opinion?

Yes. The EU should bend some of the criteria to admit other states (Serbia, Albania, Kosovo, Bosnia). Sooner or later these countries will have to enter. But there are all kinds of problems: the reluctance of some states (referendum in France), in Serbia, some (radicals) like Kostunica defend a rapprochement with Russia. We have not yet succeeded in convincing (and informing) the Serbs of all the horrors that have been committed in their name.

(interview conducted in August 2008)